In Depth: Why China’s Injured Gig Workers Often Lose Out in Court

Liu Jiwei, one of millions of drivers working for the ride-hailing company Didi Chuxing Technology Co. Ltd., died suddenly on Feb. 16, 2019, in his work-registered car. Despite two years of effort, his family has struggled to prove Liu had established a formal labor relationship with Didi or to receive compensation for his death.

Liu became a Didi driver in June 2017. His account on the Didi platform showed that he had completed 3,518 trips and earned more than 200,000 yuan ($31,024) from the job.

Didi claimed Liu had never signed a labor contract, and that his death could not therefore be considered work-related. “Didi’s attitude has always been tough. For a long time, we couldn’t find anyone to deal with the case,” said Xian Xiaoyan, the Liu family’s lawyer.

In an attempt to prove Liu had a labor relationship with Didi, his parents and wife applied for labor arbitration, filing lawsuits before the courts. But nothing worked.

The case is just one story that exposes gaps in China’s legal system regarding labor, which mainly protects the rights of employees with formal labor contracts — the key to ensuring they have established a labor relationship with employers.

Millions of Chinese gig workers, including takeout and ride-hailing drivers, are facing trouble safeguarding their rights because they don’t have labor contracts. When incidents occur, injuries are often not recognized as work-related, and the platforms they work for can refuse to pay compensation. And although some have turned to the courts to prove a labor relationship, they rarely win because they have a very different status from traditional employees in terms of working hours, organization and management.

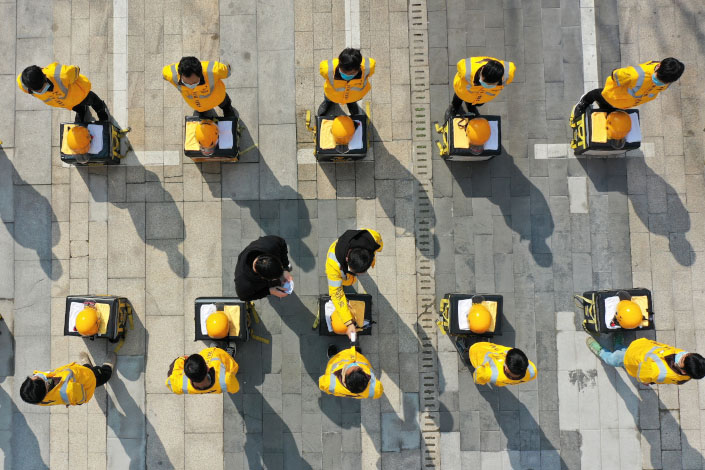

|

A labor dispute case involving 19 ride-hailing drivers is heard on April 7 in Xi’an Intermediate People’s Court in Northwest China’s Shaanxi province. Photo: VCG |

Multiple sources told Caixin that the country is working on a national pilot program that will provide occupational injury insurance for these workers. At a September meeting, Chinese regulators told leading delivery and ride-hailing firms including Meituan and Didi, both of which sources said will be included in the pilot program, that they would toughen regulations on new forms of employment.

Judicial dilemma

The reason for Liu’s relatives’ failure in court is that the current laws and regulations don’t specify the labor status of gig workers employed by the online platforms, giving the latter the option of denying their responsibility for occupational injuries.

Traditional labor relationships depend on three aspects — personal, economic and organizational — and according to Xian, Liu’s relationship with Didi pertained to all three of them.

He told Caixin Liu was assigned tasks by the ride-hailing company, and subject to its regulations and punishments, proving an organizational connection. Also, Liu’s average income from ride hailing — his only source of income — was about 10,000 yuan a month, which meant he was dependent on the company economically. Last but not least, Liu was engaged in the core business of Didi, controlled and trained by the company before starting work, which is a manifestation of organizational subordination.

Didi claimed that Liu had a cooperative relationship with the company, rather than a labor relationship, according to an appeal’s court verdict (link in Chinese).

It was not clear if their relationship could be called outsourcing, but platform enterprises often use outsourced workers to reduce costs. Such workers are hired by third-party agencies that outsource their labor to platforms. They usually don’t have labor contracts but hold a labor agreement with the agencies that pay their salaries.

A district court in the southern city of Zhuhai where the case was heard, eventually rejected Liu’s family’s claims after checking the content of the service agreement the driver signed on Didi’s app. The agreement showed that the two parties were actually affiliate partners.

Although Liu’s parents and wife appealed the decision, the Zhuhai Intermediate People’s Court, upheld the original judgment against them in May.

This is not an uncommon ruling in China. In two-thirds of cases in which a worker seeks to confirm a formal labor relationship with an employer in China, the court rules that no such relationship exists, said Li Jianfei, a law professor at Beijing’s Renmin University who participated in the drafting of the country’s Labor Law.

He also noted that in some cases, courts recognized the existence of a labor relationship as the cases involved injuries, deaths or need for medical treatment, forcing the courts to do so to avoid a potential public outcry.

In July 2016, a courier surnamed Li, who was working under a service contract with Beijing Tongchengbiying Technology Co. Ltd., was injured in a traffic accident when delivering goods in the Chinese capital. In order to obtain occupational injury insurance, Li then sued the express delivery company, demanding the classification of a labor relationship as the company had refused to recognize him as its employee. A local court hearing the case finally ruled in favor of Li, and required the company that benefited from the driver’s work to take responsibility.

Observers said it is rare to see judgments favorable to platform workers as the broad judicial attitude remains conservative. A survey by Beijing Haidian District People’s Court found that in practice, judges are not consistent in their rulings, leading to a range of results.

Pilot campaign

One of the most urgent issues faced by China’s gig workers in safeguarding their rights is whether their injuries on the roads can be recognized as work-related.

In the southern metropolis of Guangzhou, from January to November 2020, the total number of traffic accidents involving takeout riders rose 22.2% (link in Chinese) compared to a year earlier, according to government data. The number of injuries increased 8.6% year-on-year and deaths grew 133.33% year-on-year, the data show.

Li Lingyun, a professor at the East China University of Political Science and Law, said that a considerable number of labor dispute cases were brought for the identification of work-related injury. It’s necessary to establish an occupational injury insurance system outside of traditional employment relationships, Li said.

China is developing a national pilot program that will provide occupational injury insurance for workers engaged in “flexible employment,” which has become a major source of job opportunities and a driving force of national economic growth.

A person close to the internal discussion told Caixin that six or seven provinces and cities will take the lead in testing out the program, along with the participation of a list of platform companies in ride-hailing and delivery industries.

The companies include Shanghai-based delivery company Dada Group, Beijing-based delivery startup FlashEx, Hong Kong-based logistic startup Lalamove, food delivery platforms Meituan and Ele.me, as well as ride-hailing apps Didi and Caocao Chuxing.

The pilot campaign is expected to be launched in the first quarter of 2022 and last for one or two years, the person said.

The move comes after several government agencies including the Ministry of Transport in July issued a guideline (link in Chinese) calling for better protection of the rights of workers in the sprawling gig economy, including carrying out pilots of occupational injury protection for platform workers.

You Jun, vice minister of human resources and social security, said at an August press conference that the country is formulating measures on occupational injury protection (link in Chinese) for such workers, while the pilot program will start with industries that have drawn high social attention and are at high risk of occupational injury.

|

Four deliverymen take shelter from the rain in August 2020 in Jinan, East China’s Shandong province. Photo: VCG |

A person close to Meituan told Caixin that the food delivery giant is “actively” participating in the preparation of the national program. Wang Xing, Meituan’s billionaire founder, said on a conference call in late August that the company had “taken the lead in responding to the government’s call” and would implement the pilot program of occupational injury insurance for its delivery riders.

Discussion on protection

For years, Beijing is making efforts to crack down on the sprawling internet industry, with a focus on protecting the rights and interests of workers in the platform economy. In September, the country’s top regulators published a three-year plan to regulate algorithms widely used by tech platforms which have posed threats to the workers’ safety, as some, like Meituan riders, often violate traffic rules to make their deliveries as fast as possible.

The government’s efforts have triggered a discussion on how to better protect gig workers’ rights and interests, especially in the classification of their labor status.

Hong Guibin, a Shanghai-based lawyer, said bringing platform workers into traditional employment relations is one way to strengthen the protection of their rights. However, this means platform enterprises or relevant employment parties will pay huge social insurance fees for their workers, Hong added.

Take Meituan as an example. Currently, there are 1 million active delivery riders on its platform every day, a person close to the company told Caixin. According to Chinese laws, social insurance fees account for up to 40% of a worker’s total salary if paid in full. Thus, covering social insurance for all of its riders will place a heavy economic burden on the company, the person said.

As such inclusion means traditional labor legislation will intervene in the platform economy, this may lead to changes in the current business model and financial situation of the platforms, resulting in mass unemployment and damage to workers’ interests, Li said.

The July guidelines stipulated three different categories of gig workers, including one type who don’t qualify as having a labor relationship but are managed by platform enterprises. Regulators have required platforms to prepare written agreements for these workers.

This marks the transformation of the identification of labor relations from a “dichotomy” — the recognition of workers as either employees with labor contracts or as self-employed workers with no written contracts — to a “trisection” or ternary structure, said Shen Jianfeng, a professor at the Central University of Finance and Economics.

China has 7.7 million registered takeout riders, Pang Jin, an official at the State Administration for Market Regulation, said at the August press conference. According to a report (link in Chinese) by Beijing Social Work Development Center for Facilitators, only 26.5% of the more than 300 riders surveyed in May had signed a labor contract with any of the platforms they work for.

Hong said the problem of protecting platform workers’ rights can be eventually solved by clarifying their legal status as well as revising laws and regulations, while it currently remains difficult for Chinese lawmakers to amend related legislation.

Instead, the country should address the “hardest” problems first, such as occupational injury, he said, noting that carrying out pilots is the “most feasible” way out.

Contact reporter Wang Xintong (xintongwang@caixin.com) and editor Heather Mowbray (heathermowbray@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Google

Sign in with Facebook

Sign in with Facebook

Sign in with 财新

Sign in with 财新