In Depth: Want a Loan? Forget the Bank, China’s Tech Giants Are at Your Service

Click into some of China’s most popular apps these days and you’ll soon be drowning in adverts for loans.

“Borrow up to 200,000 yuan ($28,590) through Meituan’s special loan service with a daily interest rate of less than 0.02%”…. “Important reminder! The interest rate on a Didi loan is lower than what you’re paying on your credit card payments. Click here for more …”

And if you aren’t attracted by Meituan Dianping’s “Monthly Delivery” or Didi’s “Dripping Water Loan,” you can take your pick from “Xiaomi Installments,” “360 IOU,” “Baidu Blooming Wealth,” or “JD.com IOU.”

Pushing financial services, especially loans, has become the latest “big thing” for internet and tech giants as they look to leverage their huge customer base to generate more revenue and profit as growth in their core businesses slows.

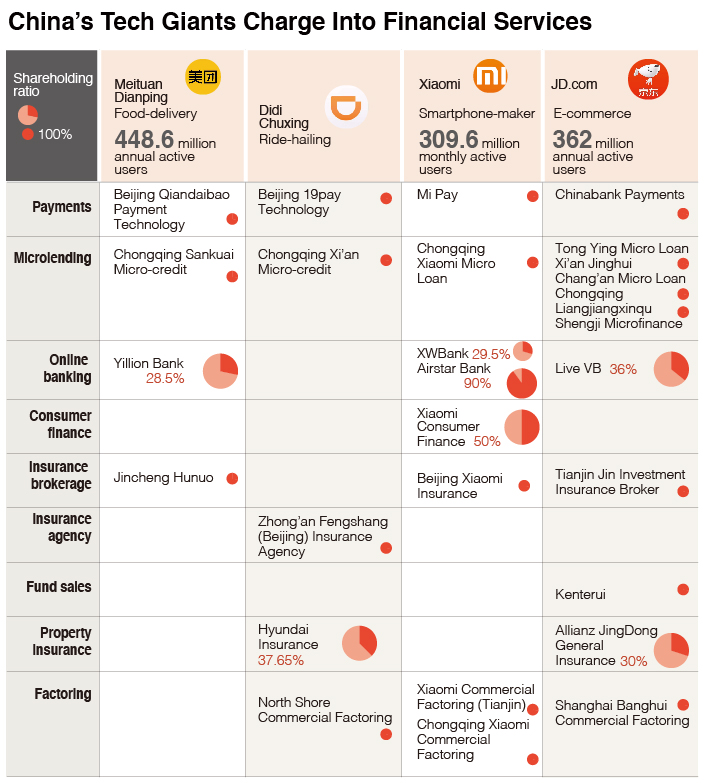

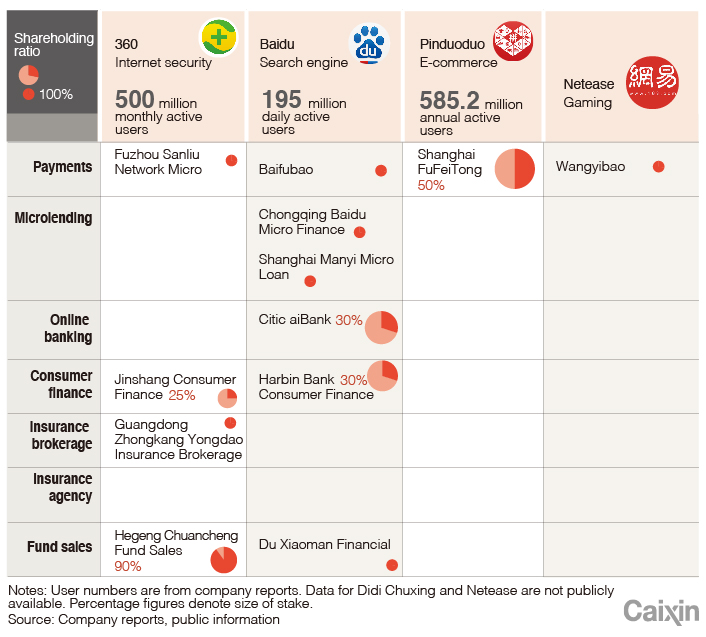

Ride-hailing company Didi Chuxing Technology Co. Ltd., e-commerce platform and online retailer JD.com Inc., smartphone maker Xiaomi Corp., and a plethora of lesser-known peers, including online discount retailer Vipshop Holdings Ltd. have all ventured into some sort of financial services provision, from micro loans and consumer loans of up to 200,000 yuan, to wealth management products, insurance and mutual-aid health care platforms.

With hundreds of millions of users, these tech giants are hoping they can replicate the success of Ant Group, the financial services affiliate of e-commerce giant Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., and entertainment and social media behemoth Tencent Holdings Ltd. Ant Group, which this week confirmed its plans for a dual listing in Hong Kong and Shanghai, and Hong Kong-listed Tencent, own the country’s two largest third-party payment platforms – Alipay and WeChat Pay – and have made billions from leveraging their customer base.

Meituan Dianping reported 448.6 million users who made transactions on its apps in the year through March 31. JD.com, one of China’s top online retail platforms, had 362 million annual active customer accounts in 2019, while Xiaomi reported 309.6 million monthly active users of its MIUI operating system in December. These customers provide a vast ocean of information that can be mined through big data analytics and used to target them with relevant goods and services or to assess their creditworthiness for loans.

Alipay and WeChat Pay have built up an unassailable lead in the third-party payments sector and control more than 90% of the market. JD.com and Meituan Dianping are among those who tried and failed to make a dent in the mobile payment space and have turned to other areas of financial services, such as online lending and consumer credit, where they have a better chance of competing and monetizing their customer base.

Qihoo 360 Technology, the country’s top internet security company known for its anti-virus software products, was one of the earliest to get into consumer lending. In 2016 it introduced “360 IOU,” a service offering customers loans of up to 200,000 yuan, the maximum allowed by regulators for online loans for individuals, repaid in installments with interest charged daily.

Meituan Dianping, China’s largest food delivery platform that’s branched out into online travel, grocery retailing and bike sharing, started offering loans of up to 200,00 yuan in 2018. In May this year, it launched an online microlending service that allows customers to borrow small amounts to pay for food delivery or for a hotel booking on its app. JD.com’s fintech arm, JD Digits, operates a similar service, offering loans for goods purchased on the group’s e-commerce platforms.

|

|

Regulators have been happy to encourage the development of online financial services by these well-known tech companies to help drive the government’s policy of inclusive finance. This initiative, which began in 2005, involves providing universal access to financial services such as savings, payments, credit and insurance at low cost to those largely cut off from formal financing channels such as small businesses, the agriculture sector, rural residents, and low-income households. In 2015, the government designated expanding such services to those known as the “underbanked” as a national strategy.

“Internet loans not only help banks to enhance the level of financial science and technology, promote their transformation and development, but are also better and more convenient to meet the reasonable consumption needs of residents and support the development of real economy,” the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission said in a statement on Friday. “As an important supplement to traditional offline loans, Internet loans can serve customer groups that are difficult to reach through traditional financial channels, and its inclusive financial characteristics are more prominent.”

Policymakers had previously backed peer-to-peer (P2P) lending as a means of broadening access to financial services, allowing the market to grow virtually unchecked from 2011 until a string of scandals and fraud triggered a crackdown in 2017. The clean-up campaign has virtually wiped the sector out, and many of the platforms that have survived have reinvented themselves as microlending companies, consumer-finance companies or loan intermediaries.

Shifting the inclusive finance strategy to draw in big-name brands that have already established their reputations in other sectors may give consumer lending and other financial services a fresh shot in the arm and at lower risk. That’s because, unlike P2P platforms, tech companies already have detailed knowledge of their customers — their consumption habits, spending behavior and creditworthiness.

“China’s high rates of digitalization and its outsized e-commerce market have produced a vast amount of data that can facilitate development of the consumer fintech industry,” S&P Global Ratings analysts led by Fern Wang wrote in a report last year. “For example, data analytics or artificial intelligence programs could allow for borrowers’ financial status to be gauged in a few seconds, making instant credit approval possible.”

Risk-free lending

Ant Group and Tencent have so much information about their users that they’ve been able to develop their own credit scoring systems. Tencent, for example, gives users scores based on WeChat payment history, credit records and verified personal information. Those with solid credit records can enjoy “use first, pay later” privileges, deposit-free rentals of shared bikes and power banks. The credit system is supported by over 1,000 services from hotel bookings to supermarket purchases.

Some tech companies initially funded their lending operations by teaming up with banks who provided them with financing in return for a cut of the profit. It was almost risk-free lending for the banks, who basically outsourced the entire lending process to their partner. The tech firm put money into a risk guarantee fund that compensated the bank for any losses incurred through bad debts. It also took responsibility for promoting the service, risk management, and assessing borrowers’ creditworthiness. But as regulation has tightened up and tech companies have grown stronger, they are increasingly funding the business with their own money or by pressing banks to share the risks as well as the profit.

Wu Haisheng, the head of Qihoo 360’s finance arm, told Caixin that he expects 35% to 40% of its lending business will use the risk-sharing model and that the profit will be split 30:70 in favor of the bank.

These can be win-win partnerships: tech firms have millions of users, detailed information about their customers’ spending patterns and creditworthiness, and efficient distribution channels, but often lack the necessary regulatory approvals and funding. Banks, especially small-to-midsize lenders lack the relevant technology, innovative capabilities and distribution networks to grow their exposure to consumer finance loans but have plenty of money.

Many banks were initially reluctant partners, worried about the risks of making unsecured loans, according to Xiaomi, which provides credit to independent smartphone retailers in smaller towns to encourage them to promote its products.

Hong Feng, the chairman of Xiaomi Finance, told Caixin that initially, even though it touted customer data as a selling point to persuade banks to cooperate, they were unenthusiastic about providing funding for Xiaomi to make loans because they were concerned about the creditworthiness of the retailers. To solve the problem, sensors were installed in the drawers retailers used to keep their stock of phones, allowing Xiaomi to track and monitor how many smartphones they were selling. It then let the banks use the data to calculate the retailers risk profiles, according to Feng.

Ant Group and Tencent have shown that over the longer term, financial services targeted at consumers can be highly profitable. But companies like Xiaomi, JD.com and Didi Chuxing are relatively new entrants and as such have had to bear significant costs as they invest to scale up their businesses while sales and profits are still relatively small.

|

At a supermarket in Beijing, a customer uses a self-check out machine to scan a code to pay for her purchases. |

Early days

At the end of March 2020, 360 Finance had outstanding loans of just 73.2 billion yuan, Xiaomi Finance’s outstanding loans, including co-lending with banks, was just over 30 billion yuan. Meituan Dianping’s loan balance currently is just over 60 billion yuan, and Didi Finance’s loan balance is more than 50 billion yuan, sources familiar with the matter told Caixin. By comparison, Shanghai- and Hong Kong-listed China Merchants Bank Co. Ltd.’s total loans and advances to customers amounted to 4.7 trillion yuan at the end of March 2020.

The contribution of financial services to the overall business is so low that many have yet to start breaking them out in their earnings reports, but information that is available show some are making a good return. Xiaomi reported that its gross profit margin from internet services rose to 63.7% in the fourth quarter of 2019 from 62.9% in the previous three months, mainly driven by its advertising and fintech businesses.

Last year, Shanghai-listed 360 Technology reported net profit of 6 billion yuan on revenue of 12.8 billion yuan. Its Nasdaq-listed financial affiliate 360 Finance reported net profit of 2.8 billion yuan on revenue of 9.2 billion yuan. An industry source told Caixin that 360 Finance’s revenue comes mainly from 360 IOU.

Yet even as consumer lending and microlending boom, it’s becoming more difficult to enter the financial services market as regulators, who initially took a relatively relaxed approach toward fintech to promote its growth, are now tightening up amid the government’s ongoing campaign to curb financial risks and bad debts.

Tech companies who want to use their own internal funds for consumer lending need a license from the Financial Regulatory Bureau in the city or province where they are headquartered. Bytedance Ltd., the owner of Chinese short-video app Douyin, which has more than 400 million daily active users, has been unable to secure any financial service licenses. Instead, it has resorted to selling advertising space to financial companies on its popular news aggregator app Toutiao. Pinduoduo Inc., a Groupon-like e-commerce platform focused on selling low-cost goods, is still looking to obtain a license to carry out microlending, a source familiar with the matter told Caixin.

There are also growing concerns about data privacy and how companies are using, or abusing, the trove of information they collect from users.

Applicants for Didi’s “Dripping Water Loan” for example, are required to sign an agreement allowing the tech company to collect data including their name, phone number, home address, biological characteristics (such as fingerprints and facial features for facial recognition), purchasing records from the Didi app and the IP addresses of their smartphone and computer. The agreement also allows Didi to collect user data such as credit and debt records, and their personal financial situation — such as tax payments, investments in stocks and bonds — from third-party institutions such as banks and judicial authorities.

One common practice is for online lending apps to demand users accept — often unknowingly — lengthy user agreements that include terms such as authorizing the extraction of users’ contact lists and allowing the apps to use users’ personal information to work with third parties.

Growing headwinds

In October 2019, the National Internet Finance Association of China, an industry self-regulatory body, issued window guidance to online financial platforms to check if the data they use is in full compliance with the Cybersecurity Law, which was enacted in 2017. The China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission’s Beijing branch issued a formal document in September 2019 specifying what financial institutions can and cannot do with big data.

The first draft of a data security law had its first reading when the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress met at the end of June. When the law is eventually passed, it will be the first piece of legislation specifically covering data security and protecting individual privacy.

China’s tech companies are hoping that financial services will be a money-spinner. But as competition intensifies, regulation tightens and privacy laws curb data collection and use, the headwinds are increasing.

A former regulator told Caixin that one of the major characteristics of Internet enterprises is the pursuit of short-term benefits, and their business model doesn’t necessarily work in the financial sector, where firms need to survive an entire economic cycle and the volatility of the financial cycle before they can judge their performance.

“No matter big data or cloud computing, there is still a long way to go until they prove they’re successful in the financial field,” he said. “We have to take a long-term view, and it’s still too early to tell the story of the success of big data.”

Timmy Shen and Isabella Li contributed to this report.

Contact reporter Tang Ziyi (ziyitang@caixin.com) and editor Nerys Avery (nerysavery@caixin.com)

Caixin Global has launched Caixin CEIC Mobile, the mobile-only version of its world-class macroeconomic data platform.

If you’re using the Caixin app, please click here. If you haven’t downloaded the app, please click here.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR