Cover Story: The Rocky Path Facing Chinese Companies Tapping U.S. Markets

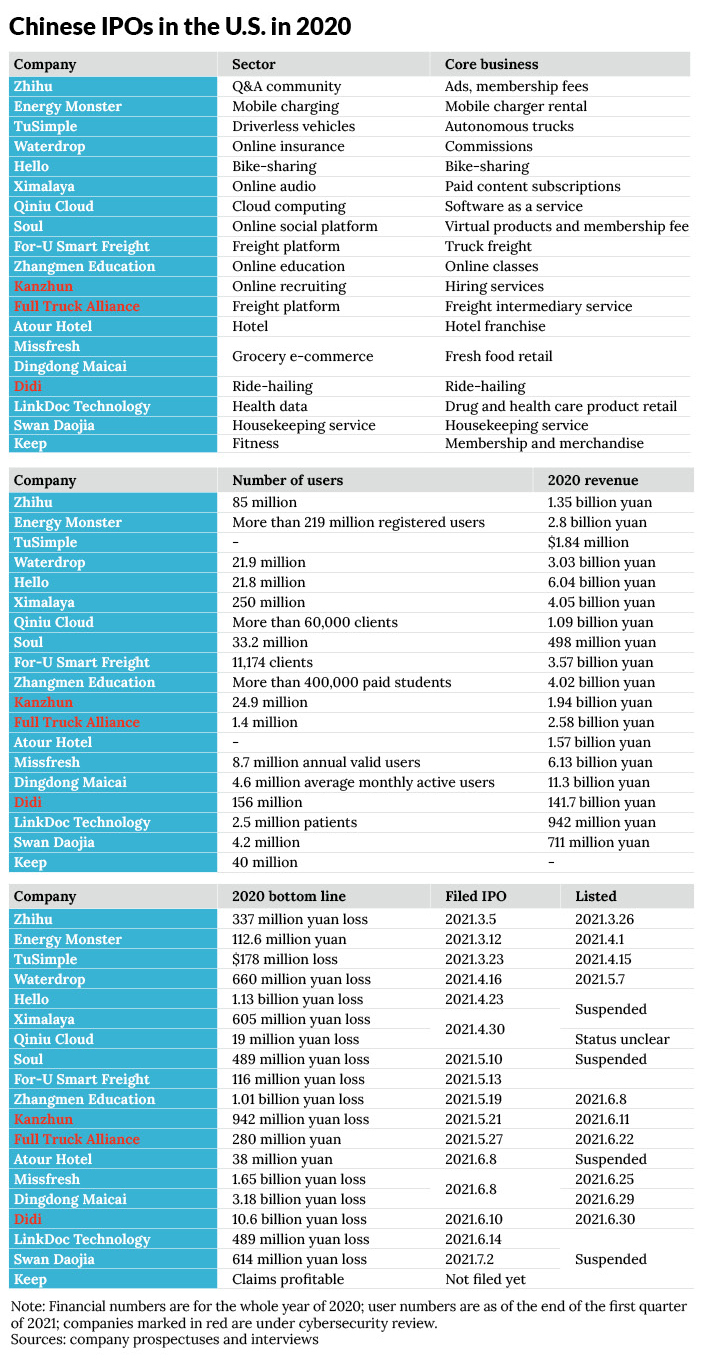

The race by Chinese internet companies to raise money in the U.S. stock market this year came to an abrupt halt after Didi’s rush to sell shares on the New York Stock Exchange without the blessing of Chinese authorities backfired.

Initial public offerings (IPOs) abroad by private companies like Didi didn’t previously require official approval by Chinese regulators, but they usually still needed an unofficial nod. By proceeding without such a signal, the Chinese ride-hailing giant wound up under national security review, its apps removed from app stores, and its shares trading 14.5% below the IPO price.

Now a newly revised regulation makes clear that any Chinese company holding the personal information of 1 million or more users would have to seek a government cybersecurity review before a foreign share flotation. Such companies should provide “IPO materials to be filed” with the Cybersecurity Review Office, an interdepartmental bureau, according to the draft regulation.

This means that in the future almost all Chinese internet companies that are eligible to go public in the U.S. will come under review. Several data-rich Chinese enterprises suspended their overseas share sale plans after the Didi fallout. Among them, audio content platform Ximalaya, bike-sharing company Hello Inc. and social network Soul all have far more than 1 million users.

The regulatory crackdown adds to headwinds facing Chinese tech companies trying to generate capital on American stock markets. The mobile internet sector was already running out of gas, with a number of Chinese companies’ U.S. shares trading well below their IPO values. And a long-running dispute between China and the U.S. over American regulators’ access to audits of Chinese businesses prompted Congress to pass a law threatening to kick noncompliant foreign companies off U.S. exchanges. That prompted some of the highest-profile U.S.-traded Chinese enterprises to obtain secondary listings in Hong Kong or China.

|

The cybersecurity reviews will focus on assessing national security risks from procurement, data processing and “overseas listings,” including the risk of core data or a large amount of personal information “being stolen, leaked, destroyed, or illegally used or exported,” according to the draft regulation. Also under the microscope will risks related to critical information infrastructure, core data or large amounts of personal information “being influenced, controlled or maliciously used by foreign governments” after a Chinese company’s overseas listing.

Before making U.S. IPOs, Chinese companies usually get “window guidance” from Chinese regulators providing a hint as to whether overseas listing plans will be acceptable, multiple market participants told Caixin.

Tencent-backed online insurance platform Waterdrop Inc. received a hint two months before its $360 million New York IPO that the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission wanted the listing postponed. Didi received similar hints. The company originally considered a Hong Kong IPO in mid-2020 but later waived the plan due to concerns that it could face harsher regulatory scrutiny in Hong Kong. The CSRC didn’t support Didi’s Hong Kong IPO, and wanted Didi to proceed with its IPO after it first resolved compliance issues such as drivers’ qualification and safety issues, said a person close to the underwriters.

Waterdrop went ahead with its IPO May 7, and Didi did so June 30, despite the warnings. Their IPOs accelerated the revision of the cybersecurity review rules.

Chinese dating app Soul filed its proposed IPO with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission in May but abruptly scrapped the plan last month just before pricing, citing “alternative financing options.” The company booked a hotel in Shanghai for a listing ceremony and sent out invitations to participants, a private equity investor familiar with the matter told Caixin.

“Why such an abrupt decision?” the investor said. “Because it knew if it went public, the next day it would be ordered offline.”

Carnival is over

Following the Didi investigation, two more domestic tech companies newly listed in the U.S. also came under review by cyberspace regulators — online recruitment platform Boss Zhipin, run by Kanzhun Ltd., and truck-booking platform operator Full Truck Alliance Co. Ltd., also known as Manbang Group. Market insiders say they think there are more companies on the review list, including all Chinese enterprises that raised funds in U.S. markets in the past three years. Several companies that were recently listed or plan to sell shares told Caixin that they haven’t received any official notice of such reviews.

But some companies and investors are looking for countermoves.

“Every day, different teams from large investors come to our headquarters, Asian-Pacific office and China office to consult on China’s policies,” a person at a Chinese consulting firm told Caixin. “Adjusting their investment strategy on Chinese companies is a long-term process, but discussions have begun over the past year or so.”

Many investors say they think the mobile internet sector, hit hardest by the new cybersecurity rules, has long lost its appeal in the IPO market, so the impact of the new crackdown may not as big as could be expected. Continuing tensions between the U.S. and China in recent years have prepared investors and U.S.-traded Chinese companies. Many such businesses have been actively considering privatization or switching to Hong Kong or Chinese mainland markets, and some companies have already moved in that direction.

“The IPO carnival of mobile internet companies is over,” said Liao Ming, founding partner at Prospect Avenue Capital, tech startup private equity firm. From 2009 to 2020, the top eight investment banks each underwrote an average of 15 Chinese IPOs in the U.S. With the new cybersecurity policy, there are only a handful of potential superstar offerings left in the sector: Chinese Uber-like freight company Huolala, Ximalaya, lifestyle platform Xiaohongshu, Hello and potentially ByteDance Ltd., the Chinese owner of popular short-video app TikTok.

All five would be subject to cybersecurity review under to the new rules because of their enormous user bases. Huolala has 7.6 million monthly active users; Ximalaya, 250 million; Xiaohongshu, more than 100 million; Hello, more than 10 million; and ByteDance, 1.9 billion globally. For content platforms, review of text is relatively easy, but video platforms face big risks in such reviews, a venture capital investor told Caixin. Under present circumstances, it would be almost impossible for ByteDance to go public in the U.S., the investor said.

It’s unclear whether enterprise service providers will face the same kind of reviews as platforms that directly serve consumers. Cloud service supplier Qiniu Cloud, which filed a U.S. IPO prospectus April 30 with the Securities and Exchange Commission, serves clients including Chinese online entertainment platform Bilibili Inc. with more than 200 million monthly active users and Xiaohongshu. Whether Qiniu Cloud falls under review will provide a clue for other enterprise service providers, a lawyer dealing with Chinese companies’ U.S. IPOs told Caixin.

“Nobody knows what the next step will be,” the lawyer said.

Starting in 2020, large Chinese tech companies such as Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., JD.com Inc., NetEase Inc., Baidu Inc. and Bilibili have been hedging against the risk of delisting from U.S. stock exchanges through secondary share sales in Hong Kong.

Privatization is another option. In March, Sina Corp., an internet portal and the parent of China’s Twitter-like Weibo, completed a management-led buyout to take China’s oldest U.S.-listed internet company private. Sina was a pioneer when it made its Nasdaq IPO in April 2000, using an unusual structure at the time to get around China’s discomfort with foreign ownership of internet companies. Since then nearly all of China’s hundreds of venture capital-backed tech companies that have sold shares in New York and Hong Kong have used a similar legally ambiguous structure, known as a variable interest entity (VIE), which involves setting up an offshore company for listing purposes.

Now Sina’s management is considering taking its U.S.-traded Weibo Corp unit. private, Caixin learned from several independent sources. Sina tapped investment banks to look for potential buyers, including its major shareholder Alibaba, according to one person close to the matter. A Weibo representative denied such reports.

For companies that still want to pursue U.S. flotations, when and how the new cybersecurity review rules take effect will be a key focus.

The revised draft measures cite as their legal basis the Data Security Law, effective Sept. 1, in addition to the State Security Law and the Cybersecurity Law mentioned in the regulation’s previous version. Several legal experts said they expect that the revised Measures for Cybersecurity Review won’t go into effect before Sept. 1.

Under to the Data Security Law, companies that do not cooperate with Chinese authorities to hand over data or that provide data to foreign authorities without the approval of Chinese authorities may face punishment such as business suspension and rectification.

The American Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (Cloud) Act, signed into law in 2018, gives the U.S. government the right to unilaterally demand access to data stored outside the U.S. that is “detrimental to U.S. national security.” This leaves U.S-listed Chinese internet platform companies stuck between the two countries’ long-arm jurisdiction.

VIE still viable?

Meanwhile, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) will be included in the national cybersecurity review mechanism, which means the Chinese securities regulator will have the right to review and approve domestic companies’ U.S. share sales.

Though it’s still not clear what role the CSRC will play in the cybersecurity review, it’s expected to carry out reviews of companies’ VIE structures, a legal director at a U.S.-listed Chinese company said.

“It simply means that there was previously no regulator to review and approve foreign listings, but now suddenly there are two,” the legal chief said.

| Sidebar: 20 - Year Path to U.S. IPOs by VIE Structure • 2000 Sina Corp. becomes the first Chinese tech firm to go public on Nasdaq with a VIE structure. • 2005 The State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) issues its “Notice on Relevant Issues Concerning Foreign Exchange Administration for Domestic Residents Engaging in Overseas Financing through Round-Trip Investment via Special Purpose Companies,” commonly known as “Circular 75,” recognizing the legitimacy of overseas financing by red chip enterprises. • 2006 SAFE, together with five other regulators, requires domestic approval of overseas listings via special purpose companies but leaves the door open for listings via VIE structures. • 2011 Alibaba’s spin-off of Alipay causes a public dispute with two of its largest shareholders and raises concerns about VIE companies’ governance. • 2020 Luckin Coffee’s fraud scandal puts the spotlight on the jurisdiction right of VIE companies. • 2021 The State Council issues the “Opinions on Strictly Cracking Down on Illegal Securities Activities in Accordance With the Law,” stating that China will take steps to crack down on securities violations, including amending the rules that cover Chinese companies' overseas fundraising and IPOs. |

Under VIE structures, an offshore entity usually incorporated in a tax haven like the Cayman Islands controls the business operator in China through a complex web of legal agreements. Unless companies are restricted from creating such structures, it would be difficult to find any legal basis to directly stop companies with VIE structures from pursuing overseas flotations, the legal expert said.

Unlike private companies, overseas listings of big red chip companies, or foreign-incorporated entities of large state-owned enterprises, require joint review and approval by the CSRC, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Commerce and the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission.

The future regulatory path could apply the same approval requirement to private VIE companies, said Jin Youyuan, a partner at China’s Merits & Tree Law Offices. As long as companies meet domestic requirements on data security, the door to overseas listings via VIE structures is still open, Jin said.

Contact reporter Denise Jia (huijuanjia@caixin.com) and editor Bob Simison (bobsimison@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR